Snapshot in the dark: How Philly counts its homeless

Many of the city’s homeless are not on the streets on a rainy winter night

By Allison Beck and Julius Philp

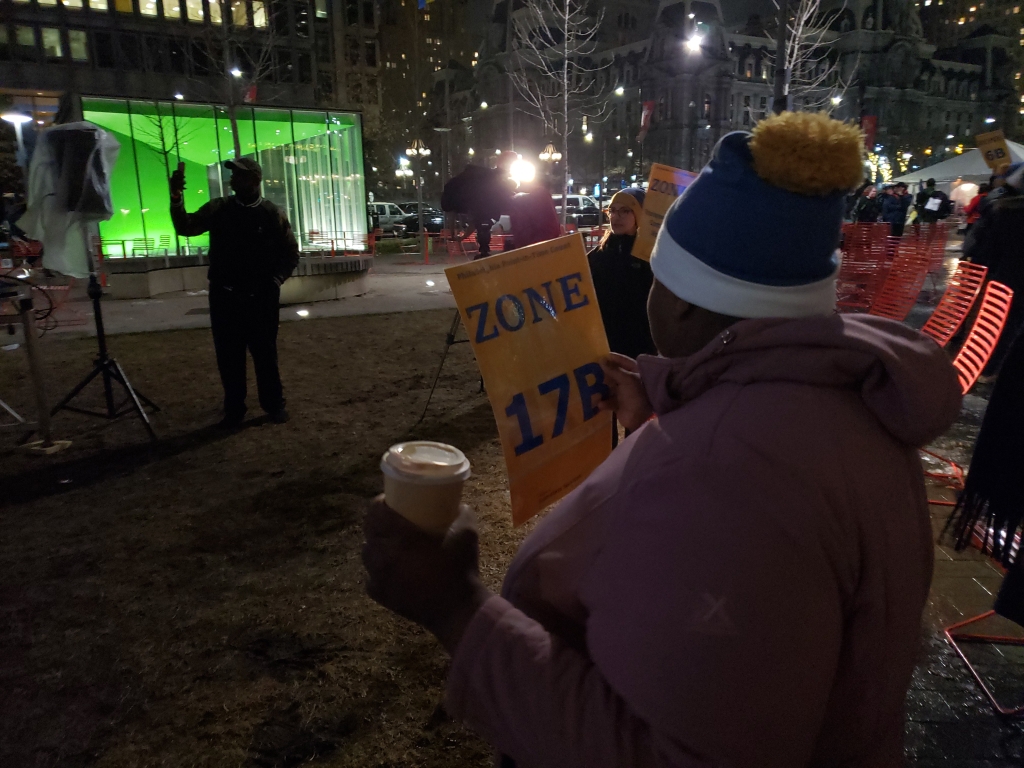

On one night in January every year, hundreds of people gather in Love Park blasting pop music and eating french fries and chicken tenders from a brightly lit food truck.

They aren’t there for a party– they’re volunteers at the annual Point in Time Count, where volunteers fan out across the city to count how many people are living on the streets. Their totals are combined with shelter counts to gauge the city’s unhoused population.

The PIT Count is mandated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and is used by federal, state and local governments to help determine program success and funding for communities across the country.

But, advocates, experts and workers in the field don’t always see it as a fair barometer of homelessness.

“One of the greatest numbers of people that are experiencing homelessness are not necessarily the people you see on the street,” said Marisol Bello, the executive director at the Housing Narrative Lab, a non-profit whose mission is to lift the voices of the unhoused. “Those are severe and chronic issues that we need to address and the breadth of homelessness is so wide and so varied that there are people that are working full time that experience homelessness and housing insecurity.”

Multiple studies in cities across the country, including New York City, Chicago and Houston, have shown that not only does the PIT count miss people that it is intended to capture, but it excludes those living in their cars or abandoned buildings and those in temporary living situations like motels and doubling up.

“Like that famous meme where you have you can see the iceberg, but then you see under the water there’s this ginormous piece of ice,” Bello said. “We’re addressing the tip, and we’re not really addressing or even measuring how big the iceberg is underneath.”

By 2023 PIT count measures, there were 4,725 unhoused people in the city, 784 of them children. However, experts and estimates from other sources say the real scope of the problem is much larger.

“For those of us who are working in this space, that really doesn’t come close to the number of homeless young people that are out there who are finding all sorts of creative ways to avoid being found,” said David Fair, the executive director at Turning Points for Children, a youth advocacy organization in Philadelphia. “We believe the city needs to look at other data that exist that identify much larger numbers of young people.”

Other parts of the government use more comprehensive measures to measure homelessness. For example, Philadelphia school district data from 2022 identified about 4,600 children as being unhoused at some point over the course of that school year, nearly six times more than the PIT estimate.

Doubling up is one of the most common ways that people experience homelessness. It happens when a person or group of people are unable to afford their own housing and are forced to live with others, often leading to overcrowding.

Doubling up was in the news in 2022 when a fire in an unsafe Fairmount public housing unit killed three women and nine of their children. Only two of the 14 residents of the four-bedroom apartment survived.

It’s also one of the experiences of homelessness that isn’t considered in the point in time count, which is why researchers from the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless and Vanderbilt University created a way to measure it using publicly available data.

With the help of those same researchers, Logan Center reporters found that between 21,000 and 38,000 additional people are highly likely to be living doubled up in the city based on data from the most recent census and American Community Survey. This estimate doesn’t account for many other kinds of homelessness, or those missed by the PIT, so the real numbers could be even higher.

While experts say that HUD is unlikely to change course anytime soon, communities can choose to gauge success and distribute funding as they see fit. The city of Chicago, for example, has used data from the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless to address the problems missed by the point in time count.

“We’ve seen doubled up homelessness is starting to be funded alongside street and shelter homelessness,” said Sam Paler-Ponce, the interim associate director of city policy at the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. “I don’t think that would have been as possible without a measure to describe the total scope.”

In the end advocates say that an accurate measure is only the beginning. A recent report by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University found that the number of renters who spend over 30 percent of their income on housing is at a record high and continues to climb.

“The more people struggle to afford to keep up with the rent, the more we are directly going to see more people struggling with homelessness and housing insecurity,” said Bello. “The natural consequence of not being able to afford a place to live when you don’t have a doubled up situation is that you’re going to end up on the street.”

Published April 9, 2024